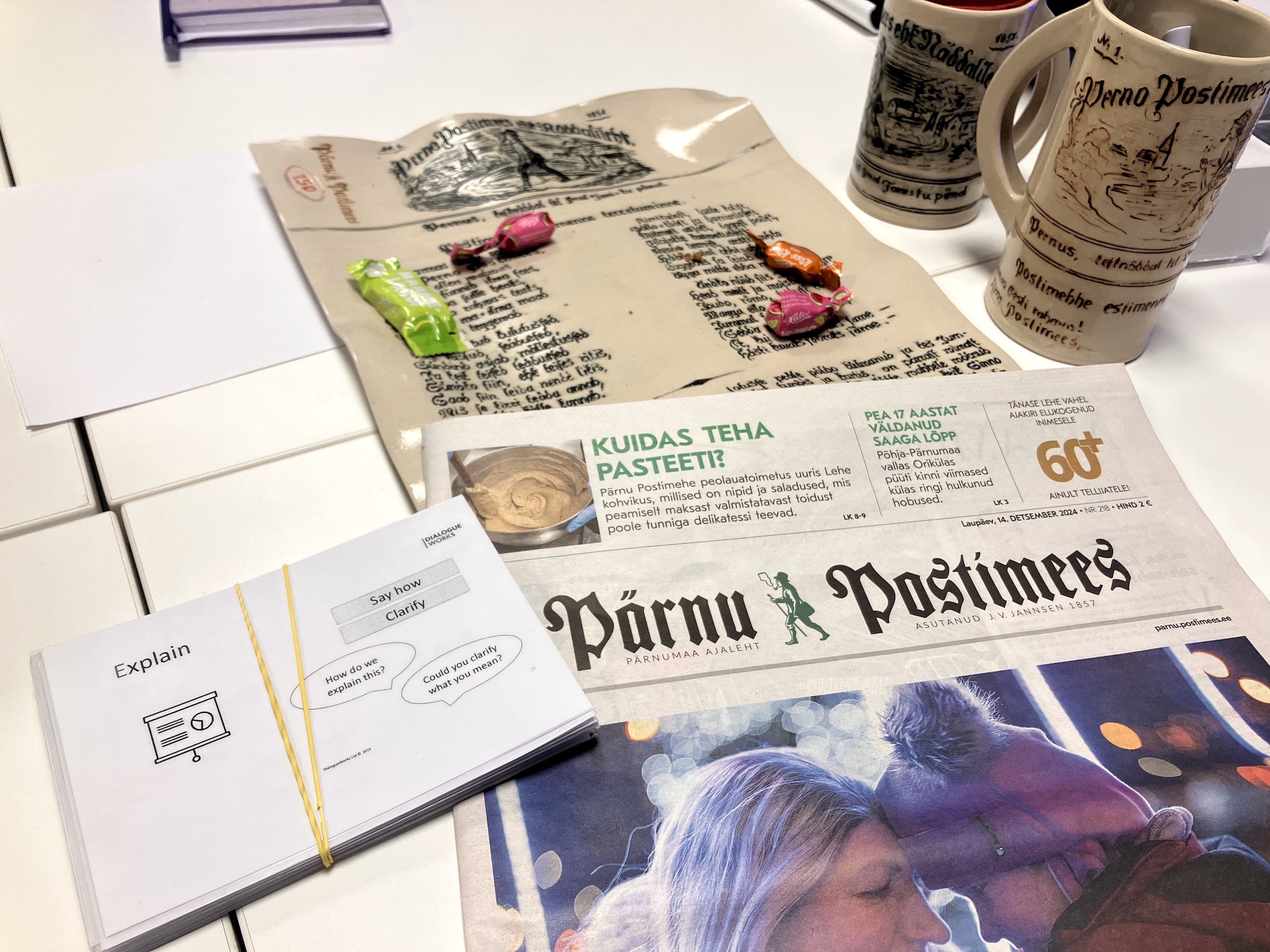

The goal of this paper is to give tips and suggestions how to use basic principles of dialogue in journalistic work. It is a follow-up of a workshop on dialogue we facilitated for the editorial team of the Pärnu Postimees newspaper in Estonia.

Practical use

Be Socrates

Adopt the approach of Socrates in ancient Athens: reflect on what people say by questioning their statements and testing their arguments. The goal is not to question everything, but to verify whether what people claim is true. People often make assumptions that they believe are common knowledge. They hope that you will simply accept them, particularly when talking to politicians, directors, and other people in positions of power. So, ask questions such as:

- What do you mean with that?

- Why do you say that?

- Why do you believe that?

- Why is that that a good thing?

- If we all do that, what would happen?

- Can you give an example?

Tip: when you are not satisfied with the answer you get, just continue asking ‘why’ questions until you get to the answer you are looking for. Don’t be afraid that people start finding this irritating. Often you are helping them to make sense of their own thinking.

Question the foundations

To understand better how your guest is looking at life, whether it is from a professional or personal perspective, it can be helpful to have them talk about the foundations of their ideas and standpoints. When you talk about public safety for example, you can say: ‘How will your party make sure people feel more safe at night?’. But that is an operative question. You ask your guest to directly say how they will solve a public issue.

An other approach can be, when introducing the topic of safety in your conversation, is to first go go to the foundations of their world view. Like for example: ‘What does a safe town mean to you?’ This challenges your guest to start thinking on this fundamental level. When they quickly want to talk about concrete policy proposals, their request talking point, go back to your previous question and be persistent, until you get an answer you are satisfied with.

Ask for examples

Building on the previous question regarding examples, this relates to a fundamental concept of dialogue: the application of practical knowledge. This type of knowledge differs from scientific knowledge, which comes from research and scientific institutes. It is the knowledge that we all develop throughout our professional and personal lives.

In public discussions, we often stay at a conceptual level. As a journalist or interviewer, you can change this by asking speakers to illustrate their statement with an example, shifting the level from conceptual to concrete or personal. For example, you could say:

- ‘You just said that you want the administration to be more efficient. Can you give a concrete example of what that looks like in real life?’

- Or ‘Can you give a concrete example of how you were more efficient as vice-mayor?’

- Tip: When your guest answers with a hypothetical example or one from someone else, tell them that you want a first-hand example. Only then will your guest draw on their own personal experience.

Stimulate thinking together

Where possible, step out of the traditional journalist-politician or interviewer-interviewee dynamic. This means changing the roles so that you ask the questions and the guest gives the answers. You can do this, for example, when the topic is not yet clear. You could also do this when there are different possible approaches to dealing with a political or policy matter. This also enables you, as a journalist, to share your personal observations and experiences. For example, you could say:

- ‘Let’s think about this out loud: From which angles can we look at this issue?’ This encourages your guest to take a step back and think. You can use your own ideas here as well, to show that you try to be equal for a moment, brainstorm together.

- For example, you could introduce it like this: ‘What other perspectives on this issue could be relevant?’ or ‘Who else could be affected?’ This encourages people to consider what or who has been missing from the discussion until that point.

Reflect at the end

Often times a dialogue ends with a moment of reflection. Questions that can be relevant are: How did the conversation go? Did we cover all the important topics? Did we find meaningful answers to the main questions? Did we miss any viewpoints? Was everyone included? You can also ask such questions at the end of an interview or podcast.

This gives your guest(s) the opportunity to reflect on the conversation and take ownership of the content. It is important not to open new discussions, but rather to make brief observations and perhaps some additional remarks.

Background

The term ‘dialogue’ can have different meanings. For some, it refers to a conversation between two people or entities. For others, it refers to a meeting where sensitive topics are discussed gently. Some people think of dialogue as a form of negotiation. However, some people think of dialogue as a form of inquiry, investigating fundamental questions through group conversation.

There is no consensus on a clear definition of dialogue. At the same time, however, we can often identify common characteristics. For example:

- A conversation between two or more people focusing on understanding

- All participants are (more or less) equal

- Everyone can participate in the conversation

- There is a clear central question or dilemma

- People are challenged to listen carefully to each other

- Providing valid argumentation to support standpoints is important

- But these standpoints are not intended to start debating